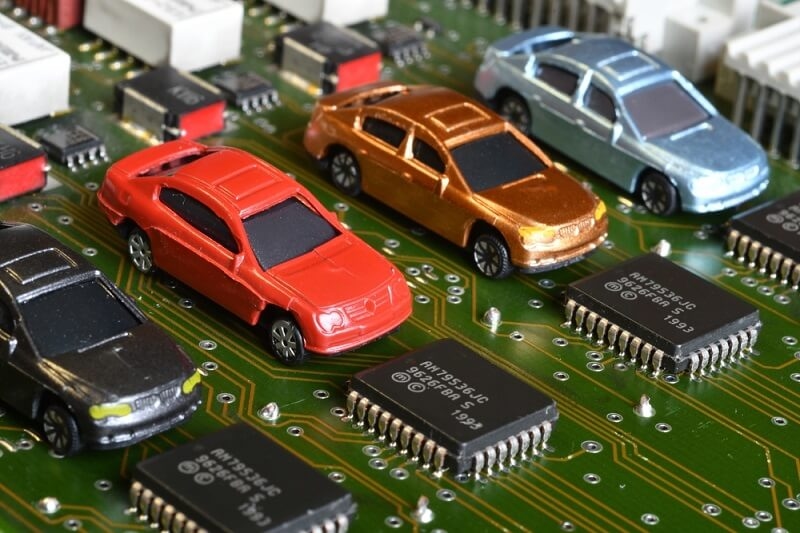

When the global microchip shortage started in 2020, many people thought it would be a year or two before it was resolved. It is now 2025, and the microchip automotive production shortage has continued to disrupt the global automotive industry, causing delays in vehicle manufacturing, postponed model rollouts, and fundamental changes in how auto OEMs order and source chips.

While chip production has improved, the increased demand for chips in all industries, especially in EVs, autonomous systems, and connected car platforms, has left automakers with a burgeoning semiconductor supply gap yet to close. This report examines how the automotive chip shortage in 2025 still creates global car factory delays, what OEMs are doing to react, and what the future holds for car production.

The beginning of the microchip shortage in the automotive industry can be traced to pandemic lockdowns, which stalled semiconductor manufacturing while the demand for consumer electronics boomed. Car manufacturers scrapped orders due to declining sales forecasts. When automotive sales rebounded faster than anticipated, the chips were repurposed for consumer electronics.

Fast forward to 2025, the chip bottleneck is less severe than its height, but it's not over. Many interconnected issues still limit the availability of automotive-grade microchips:

So what does that mean? The shortage of microchips in car production continues to put manufacturers in awkward situations, requiring them to make tradeoffs about which vehicle series to continue producing and which features to drop.

In 2025, buyers will still face long wait times for specific models, especially electric vehicles and high-end SUVs with advanced driver-assistance features. Manufacturers still lack the chips to support systems like infotainment, adaptive cruise control, and lane-keeping assist.

Many auto factory delays due to semiconductors still push vehicle delivery timelines out by 4-12 months, especially for models that use advanced chips significantly.

To meet production quotas, OEMs continue to provide models with fewer features. Popular models in 2025 are sometimes shipped without

Although this technique may be criticized, it does allow OEMs to commit the limited chips they have to key safety and drivability functions.

Although OEMs report they are committed to managing production quotas, demand is still high. Strong global demand is limiting production across automakers due to restricted chips. The supply chain challenges we have experienced through pandemic disruptions have affected auto output throughout the globe. The situation is no different in North America, Europe, and parts of Asia, where vehicle inventory levels in all regional reports in early 2025 have been suboptimal.

According to the data, as of this update, some automakers still produce 10-20% less than their pre-shortage production levels.

The rise of EVs compounds the problem. Electric vehicles typically require twice as many chips as traditional combustion-engine models due to their reliance on:

As more automakers push toward full electrification, the chip supply the auto industry requires rises exponentially, outpacing foundry expansions.

Even newer entrants like Rivian, Lucid, and Fisker have faced production stalls due to chip-related delays in 2025, limiting their ability to scale.

In the face of continued shortages, OEMs have adapted by making various strategic changes in their auto OEM chip sourcing and supply chain management.

Companies like Ford, GM, and Toyota now strike direct, long-term contracts with chip manufacturers such as TSMC, GlobalFoundries, and Intel. These deals include multi-billion-dollar investments to secure priority access to automotive-grade semiconductors.

Tesla and Stellantis have moved to integrate semiconductor design into their operations vertically. By developing proprietary chips in-house, they gain tighter control over supply and ensure their needs aren't deprioritized behind consumer tech brands.

OEMs are reducing the number of unique chips used across models. The shift to centralized vehicle architecture means fewer chips are needed overall, and standardization allows easier sourcing.

This approach helps ease dependency on niche chip suppliers and prepares vehicles for over-the-air software updates, which are crucial in modern cars.

The CHIPS and Science Act—signed into law in 2022—continues to fund domestic semiconductor manufacturing. Several fabs focused on automotive chips have come online or are scheduled to begin operations in 2025, particularly in Arizona, Texas, and Ohio.

The EU Chips Act has pumped billions into semiconductor R&D and production capacity, with new automotive chip foundries planned in Germany and France.

South Korea and Japan continue to lead in microcontroller and memory chip production. In 2025, Korea's government-supported facilities are expected to double output specifically for automotive contracts.

Still, these efforts take years to mature. While relief is expected by 2026–2027, 2025 remains a transition year with limited real-time impact.

Tier-1 and Tier-2 automotive suppliers are feeling the squeeze. Companies that produce everything from ECU (electronic control unit) to infotainment modules face volatile demand and disrupted timelines.

As a result, OEMs are bypassing some of these suppliers in favor of direct-to-fab relationships, reshaping the traditional automotive supply chain.

This shift increases costs and complexity, especially for smaller or regional suppliers without the capital to compete in global chip bidding wars.

While the supply of new cars remains strained, used car prices in 2025 haven’t fully returned to pre-shortage levels. The limited production from 2020 to 2024 means fewer lightly used vehicles are available now.

This scarcity keeps resale values high and reduces leasing availability, further frustrating consumers and dealerships.

Car dealers have adjusted to the “new normal” of low inventory and longer waitlists by:

Some even allow customers to order now and return for retrofit installations once missing chips become available.

Buyers in 2025 have become more patient and informed. Many now:

This behavioral shift also fuels loyalty toward automakers with consistent delivery timelines and transparent chip allocation strategies.

Experts suggest the global microchip crisis will continue to affect car production into early 2026, though at a gradually decreasing rate. Improvements are likely to occur in stages:

However, black swan events—geopolitical tensions, natural disasters, or economic downturns—could easily extend the timeline.

The automotive chip shortage in 2025 is still a significant challenge for manufacturers, suppliers, and consumers. While the crisis is less severe than at its peak, semiconductor shortages remain influential in automotive production.

OEMs constantly adapt, whether to streamline architectures, invest in semiconductor fabrication, or reevaluate sourcing. At the same time, consumers now have a more complicated automotive purchasing process, often with fewer options and longer wait times.

Ultimately, the automotive production microchips should remind us to build resilient, scalable, and forward-looking supply chains to advance technology. For those of us in 2025, the road ahead is paved with semiconductors, and the world is still catching up.

This content was created by AI